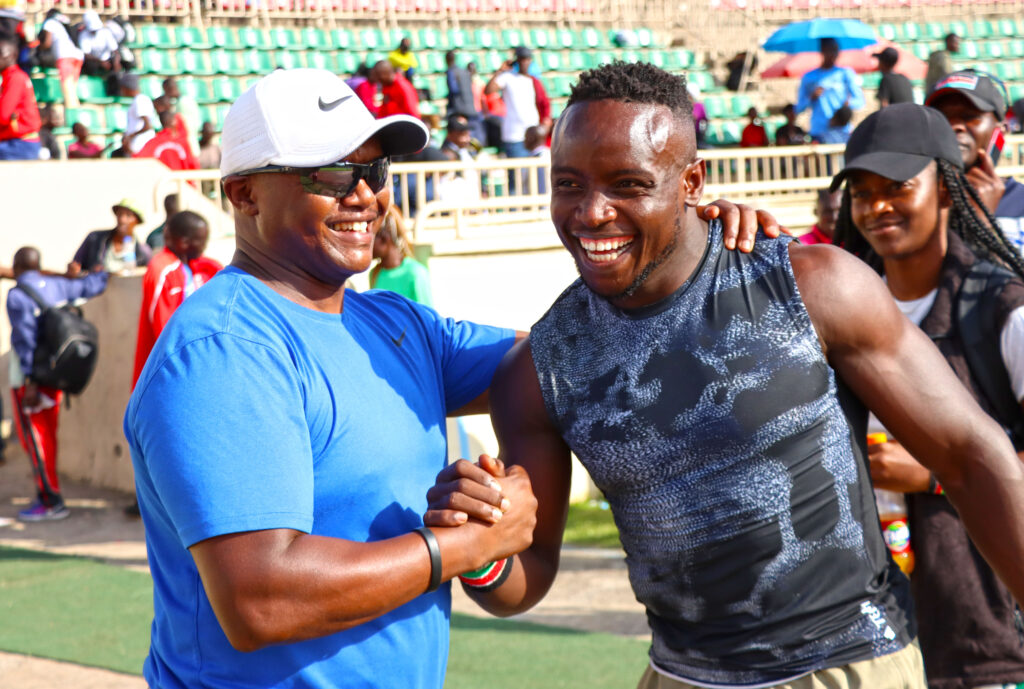

NAIROBI, Kenya, November 21, 2025 – As far as Kenyan sports is concerned, Geoffrey Kimani is a household name, a strength and conditioning (S&C) guru who struts the landscape like a colossus.

His imprints are all over the different team sports and individual athletes with who he has worked in the over 10 years he has been in the industry.

Boasting a gargantuan physique, Kimani’s profile as a strength and conditioning expert stands heads and shoulders above his peers in the profession.

He has proven to possess the Midas touch to transform athletes into a work of art and craft, chiseled and engineered to perform at optimum levels at the elite standards.

His journey to becoming the industry go-to guy for matters physical fitness began on the rugby fields of Highway Secondary School in Nairobi.

Kimani was always primed for a career in rugby but his sports teacher had other ideas that saw him veer into a career as a sprinter.

“I started off as a rugby player at Highway and the way I veered into track was funny because we had these provincial championships that were coming up. Then up on the rugby pitch, the sports teacher saw me and said, ‘call that fella and say, on

Friday, we have some provincials down at Railways Training Institute. It was for all Nairobi schools so I went there and won the 100m,” the Mlango Kubwa-born coach says.

From then on, his sprints career picked up and blew up.

He won the national junior championships title in 1992 and clinched the national 4x100m relays, among other accolades.

He also ran for the Armed Forces, specifically, Kahawa Barracks, during that same period.

Before long, he was on the plane to the United States to grow his sprints career.

However, when he got there, he had to take another detour.

Due to the challenges associated with meeting the nitty gritty of sprints, including physiotherapy and coaching, Kimani had to hung up his spikes.

It proved to be a masterstroke, a blessing in disguise as it marked the beginning of his career as a strength and conditioning expert.

“I got some networks, went to the US and when I got there, I realized it’s not

easy. People have this notion that track and field… it’s not pro like soccer. For you to be able to make ends meet, you must have a shoe contract. And a shoe contract now enables you to get money that can help you sustain things like physiotherapy, coaching and all that. So I hung my spikes when I was in Atlanta, Georgia and went into school,” Kimani recalls.

He adds: “I was lucky enough to start my journey at a high performance center in Atlanta that catered for athletes who are destined for college and also pro athletes that were on off-season. So they would come to these facilities called the Velocity Sports Performance. They emphasize on sprints, speed and power. I started with a coaching course in USA track and field. And then some courses in personal

training.”

He continued foraging books, attending a number of World Athletics courses to which he advanced up to Level Four, which has earned him the privilege to tutor other coaches in Level Two.

Selling a new concept

Returning home to a country where a strength and conditioning expert would not be a priority for many sports institutions, Kimani would have thought his work was cut out.

Fortunately, lady luck was smiling with a wide grin on him; those that he approached had had a whiff of strength and conditioning and understood its importance.

Kimani’s first port of call was then Harambee Stars head coach Jacob ‘Ghost’ Mulee who was also in charge of Tusker FC.

“It’s funny because the way I got to Harambe Stars, I went to sell the idea of speed training for soccer teams. I was selling the idea to Ghost, who was then the coach for Tusker FC. So luckily when I went to see Ghost, he had just come back from a tour of the UK and he had been to Arsenal. So he said, ‘what I want you to do is not do it for Tusker, I want you to do it for Harambe Stars’. One of the rookies in that team was Victor Wanyama,” he explains.

His next workstation was at the national rugby 7s team, Shujaa, where it didn’t take much to convince then head coach, Benjamin Ayimba, to enlist him as strength and conditioning coach.

“Benja (Ayimba) and his team manager then Oscar Osir, had just come from a professional team so whatever things that I brought on the table, they were really adaptive to them. That’s how I ended up in the Kenya 7s team,” he says.

The players took to the new training regime like a duck to water, testifying to the astronomical impact of Kimani’s methods on their physical and mental fitness.

“I am forever indebted to those players that were in that team in 2008. The likes of Mwanja (Dennis), Lavin Asego, all those guys who were there…Paul ‘Pau’ Murunga, Gibson Weru. I remember the first feedback I got was they felt muscles that they never felt that they had before,” Kimani recalls.

Success on the world stage

The results of Kimani’s work was clear for all and sundry to see as Shujaa’s fortunes on the world stage took a turn for the better.

A first-ever final in the World Rugby Series — at the Adelaide 7s in 2009 — was topped by a first ever appearance in the semi-final at the World Cup in Dubai.

The icing on the cake was Shujaa’s first ever victory in World Rugby Series, beating Fiji 30-7 to win the Singapore 7s in 2016.

Kimani remembers this period with nostalgia, admitting that it is one of his most memorable in his career.

“Seeing that team grow from 2009 all the way to a very first final in Adelaide and

then the cup win in Singapore. Singapore was one of the biggest highlights and I

remember Benja the following morning coming to my room and saying, ‘thanks man, look at where we’ve come from.’ I remember him saying we are going to win the World Cup,” he recalls.

It was not only about their success on the pitch but also the wholesome, winning mentality they imposed on the players.

Kimani reveals an unwritten rule that required all players to advance their education, in addition to playing the game.

“If you’re playing for Kenya Sevens, you had to be either in school or you’re doing something because you can’t just train for one hour and then you’re all over the city roaming and everything. So Benja and the senior players were always very particular that apart from just being a rugby player, you have to do something to set you up to become somebody else in life,” Kimani reveals.

Additional opportunities

After the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Kimani stepped down from his position at Shujaa to pursue other opportunities.

Having learnt from the mistakes made in the preparations for the quadrennial event in Brazil, Kimani approached the National Olympic Committee of Kenya (NOC-K) with a roadmap for the Tokyo games.

NOCK bought into the idea and enlisted him as a lead consultant in charge of strength and conditioning.

His role was pivotal in preparing Team Kenya at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic during which athletes were required to train in bubbles to avoid contracting the virus.

Kimani played a pivotal role in preparing an overall strength and conditioning programme for Team Kenya ahead of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

His focus was on minimising the occurrence of injuries while maximising on the fitness of all the athletes.

“That’s how I ended up working with our national boxing team and then also the Malkia Strikers. Your job also involves making sure that we have fewer injuries and the least injuries during our games,” he explains.

Another key success of his longstanding career is sprinter Collins Omae who he helped transition from rugby to the track and field.

His first task with Omae was to help him find his footing in a new discipline.

“I brought him down from the 400m to the 200m, first of all, and the 100m so that he could understand the fundamentals of sprinting and the following season he became the national champion in the 200m. Then after that, we moved over to the 400m and he won the national title and qualified for the World Championships in 2017. He also went to the Commonwealth Games, twice,” Kimani recounts.

Advice to younger self

Taking a trip back to the past, Kimani believes he is wiser than in his 20s.

A piece of advice he wishes the 20-year-old Kimani knew is to just live in the moment.

“Just take life easy…we talk so much about what we want to be in the next five years, 10 years or even plan. But first of all, live for the moment. Do what you’re supposed to do for that moment,” he says.

Regardless, the 20-year-old Kimani would be proud of how far the older version of him has come.

He has carved his name in Kenyan sports as one who has not only forged promising talents into elite athletes but also opened a career pathway for retired sportsmen and women in the country.

And to imagine that all this began at the end of a chapter as a promising sprinter.