NAIROBI, Kenya, Jan 8 — The recent claim by Prophet David Owuor that HIV/AIDS can be “miraculously healed” through spiritual intervention has reignited a fraught national debate over the balance between religious freedom and public health in Kenya.

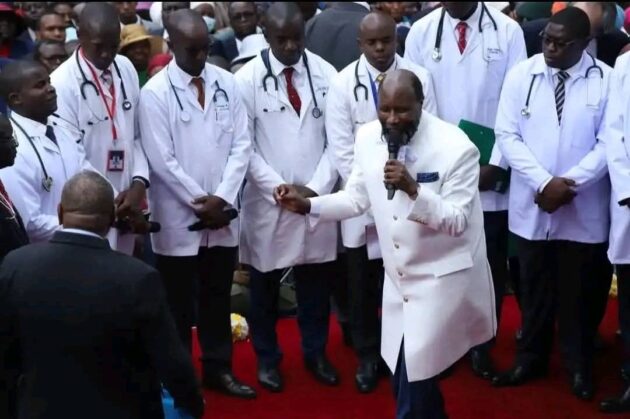

The controversy erupted on New Year’s Eve at Menengai Grounds, Nakuru, where Owuor presented a group of licensed medical practitioners who publicly claimed that multiple patients had achieved undetectable viral loads following spiritual treatment.

The claims have immediately raised red flags for Kenya’s health authorities. Health Cabinet Secretary Aden Duale condemned the use of medical credentials to lend credibility to unverified faith-based interventions, calling it “a danger to the nation” and ordering a full-scale investigation into the implicated doctors.

The Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists Council (KMPDC) has launched a forensic review of clinical documentation presented during the crusade, signaling a rare intersection of medical oversight and religious practice.

The public dispute has deeper implications than a single miraculous claim. It comes against the backdrop of the Religious Organizations Bill of 2024, legislation designed to enforce government oversight of religious entities following tragedies such as the Shakahola massacre.

Advocates argue that the bill is necessary to prevent the spread of harmful misinformation, protect citizens from unverified miracle cure claims, and ensure that life-saving therapies—like antiretroviral treatment (ART)—are not abandoned in favor of spiritual remedies.

However, critics, particularly within the clergy, view this regulatory push as an infringement on constitutional religious freedoms. They argue that faith-based interventions are protected under the law and that imposing strict oversight could amount to state interference in spiritual matters.

Owuor’s ministry has remained defiant, emphasizing that adherents will continue to undergo medical testing every two years but insisting that spiritual authority surpasses secular scrutiny.

Analysts warn that the clash illustrates a fundamental tension in Kenya’s socio-political landscape: the state has a legal and ethical obligation to protect public health, while the country’s vibrant religious communities enjoy significant constitutional protection and social influence.

How authorities navigate this conflict could set a precedent for future interactions between faith-based organizations and regulatory bodies, particularly when claims of health miracles are involved.

Beyond legal and ethical concerns, the episode has implications for public trust in medicine and governance. If miracle cure claims gain traction without rigorous validation, they risk undermining decades of progress in managing chronic diseases such as HIV/AIDS.

Conversely, overly aggressive regulation could alienate religious communities and provoke public backlash, complicating enforcement efforts.

The ongoing investigation by KMPDC, coupled with renewed debate over the Religious Organizations Bill, underscores the high stakes of this confrontation.

Kenya faces a delicate balancing act: upholding the right to religious expression while safeguarding public health in a country where both spheres are deeply intertwined.