NAIROBI, Kenya, Sep 22– German philosopher Karl Marx once described religion as “the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world … the opium of the people.”

Writing in A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right (1844), Marx argued that religion was a tool through which ruling classes controlled societies.

Nearly two centuries later, his observation still sparks debate — and resonates in many ways across Africa.

In Kenya’s capital, Nairobi, the rise of hundreds of churches within single neighborhoods raises pressing questions: Are they simply spiritual refuges, or do they mirror deeper struggles of poverty, politics, and survival?

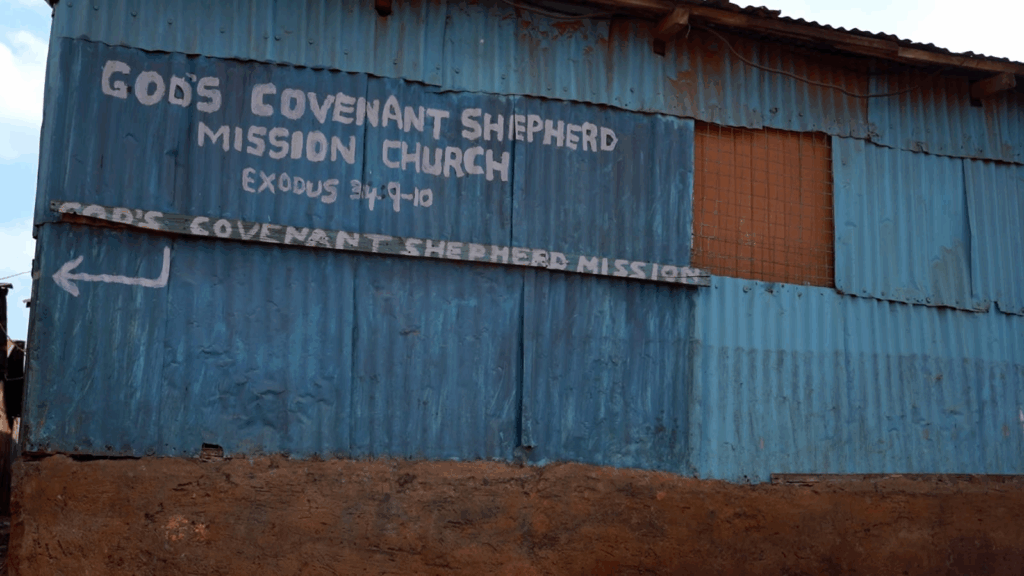

A casual stroll through Nairobi reveals a startling reality: churches mushrooming on almost every corner, often in low-income neighborhoods.

In Uthiru’s Kosovo area, which straddles Nairobi and Kiambu counties, more than 300 churches occupy a two-acre stretch.

In informal settlements such as Mukuru kwa Njenga, dozens of churches jostle for followers, sometimes separated only by a wall or iron sheet walls that form their walls.

While critics dismiss the surge as little more than a business boom in religious clothing, pastors insist their mission is spiritual.

“This is not a business,” says Pastor David Likoko of Uthiru’s New Life Neighbour Christian Church, insisting that churches have brought peace and order to areas once notorious for insecurity.

Prosperity gospel vs economic decline

Earlier in September, a five-day religious gathering at Nairobi’s Uhuru Park, described by organizers as a “non-denominational apostolic movement,” ignited heated debate both online and offline.

While some hailed the mega event as a spiritual awakening, others criticized it as yet another example on the use of religion to control and manipulate the public.

On social media, one X user argued that the growth of prosperity gospel mirrored Kenya’s economic decline.

“Prosperity gospel growth is inverse to economic growth, so this is just the beginning. We are experiencing the same decline Nigeria faced after Goodluck Jonathan left office.”

The event drew thousands, including Nairobi Governor Johnson Sakaja, Embakasi East MP Babu Owino, and Government Spokesperson Isaac Mwaura — underlining the enduring pull of politics to the pulpit.

Another critic dismissed the event, dubbed Rhema Feast, as a distraction from pressing national issues:

“It was just another display of blind faith, selling heaven and hell while unemployment and corruption remain unsolved. We need logic, not fantasy.”

But defenders pushed back, framing the backlash as spiritual warfare.

“Rhema Feast has really annoyed a lot of people on this app — a clear indication of how Satanic systems are being disoriented. The presence of God is pure joy. Kenya for Jesus,” wrote one supporter.

Why informal settlements

So why do churches multiply more rapidly in slums and informal settlements than in affluent suburbs like Karen or Runda?

For many city residents battling joblessness and rising living costs, churches offer more than prayers.

They provide food, school-fee assistance, counseling, and — perhaps most importantly — a sense of belonging in otherwise harsh urban conditions.

“Instead of going to the club to look for husbands, women can find guidance here,” Everlyn Mwende says.

“If I see my neighbor struggling, I call her and bring a pastor to help. Churches have supported us in raising children, even educating them.”

Such stories illustrate what scholars and sociologists have long argued: religion flourishes in contexts of poverty and uncertainty.

In the absence of reliable state support, churches step in as de facto safety nets — and for many, they are lifelines.

Church and politics

Kenya’s political class has also fueled the church boom.

Politicians frequently use pulpits to mobilize support, especially during election seasons.

Before his 2022 election, President William Ruto leaned heavily on church networks as campaign platforms.

More recently, his government appealed to religious leaders to help calm the Gen Z protests, underlining the state’s reliance on the pulpit for legitimacy.

Yet this close embrace has sparked criticism.

“In my view, places of worship have been turned into places of business,” Faith Masita, a youth in Nairobi, says.

“Church leaders open their doors to politicians who donate money, then manipulate congregations to support them.”

Ruto, who brands himself a “friend of the church,” has repeatedly defended political involvement in worship spaces.

“Kenya must know God so that is why we shame the people telling us not to associate with the church,” he said during a March 2024 service in Eldoret.

He has dismissed suggestions that politicians attend services for publicity.

“We don’t come to church to play politics, we know where to play politics or look for votes, when we come to church, it is because we have a plan to go to heaven.”

“We are very unapologetic about our faith in God and we are not in church to look for fame or to look for votes. We come to church because we are Christians and we believe in God. In any case, the Constitution of Kenya, the first chapter, says God of all creation.”

The unchecked proliferation of churches has however raised safety and ethical concerns.

Cults and exploitation

The 2023 Shakahola tragedy — in which more than 450 died under preacher Paul Mackenzie’s starvation cult — exposed how unregulated religious movements can prove to be a force for evil.

Just this July, another fasting-to-death cult was uncovered in Kilifi’s Binzaro area, reigniting debate about regulation.

Beyond such extremes, critics point to noise pollution from loudspeakers, lax registration rules, and the commercialization of faith through “prosperity gospel” teachings.

Vulnerable populations, critics hold, are often pressured into giving tithes to sustain pastors’ lifestyles.

In the wake of the Shakahola cult deaths, a parliamentary initiative to regulate religious institutions in a bid to shield citizens from exploitation reignited the debate on freedom of worship — a right guaranteed by Kenya’s Constitution.

Clerics opposed to regulation termed the Religious Organizations Bill which proposes improved oversight, financial transparency, and accountability as a tool for State control.

In July 2025, the Cabinet approved recommendations from a presidential task force, including the creation of a Religious Affairs Commission, leadership standards, reforms to religious broadcasting, and civic education to counter extremism.

As focus shifts on the legislative reform, it remains unclear whether the government will marshal the political will to protect worshippers against exploitation and avoid the repeat of cult deaths.

For Nairobi’s faithful, however, the proliferation of churches tells a story that extends beyond Marx’s 19th-century critique.

They are not merely instruments of control; they are survival mechanisms, political arenas, and, for many, the only institutions that make life in the city bearable.