Since returning to the White House for his second term, President Donald Trump has revived his hallmark “America First” economic doctrine—this time with even greater intensity. Central to this approach was a bold tariff plan: a proposed 10% universal tariff on all imports and a staggering 145% levy on Chinese goods. Proponents argued these measures would revitalize American industry and reduce reliance on foreign manufacturing. However, the global response—especially from the Global South—has been one of deep concern, as such policies risk unraveling supply chains, increasing costs, and exposing vulnerable economies to severe shocks.

In a significant turn of events, the recent Geneva talks between the United States and China yielded an unexpected breakthrough. After months of escalating rhetoric and retaliatory tariffs—reciprocal rates had surged past 125%—both nations agreed to a phased reduction of select tariffs, aimed at stabilizing global markets and restoring some degree of predictability to international trade. While broader structural issues remain unresolved, and both sides stopped short of a full rollback, the Geneva agreement marked a tentative de-escalation that analysts hope will prevent a full-blown trade crisis.

President Trump described the move as a “strategic recalibration” to give U.S. businesses room to adjust, while Chinese officials emphasized the mutual benefits of a “balanced and fair” trade relationship. The initial reductions—set to begin within 60 days—will primarily target industrial goods and critical supply chain components. This softening of Trump’s previously uncompromising stance suggests a rare convergence of interest in global economic stability.

The Geneva talks—held under the auspices of the World Trade Organization (WTO)—offered a faint glimmer of hope amid rising tensions. Though no binding agreement was reached, both sides committed to keeping diplomatic channels open and advancing de-escalation through technical negotiations and sector-specific discussions. China expressed concern about the disproportionate nature of U.S. tariffs and their global spillover effects, while the U.S. reiterated that its measures are essential for national economic security. The outcome may not have delivered concrete policy shifts, but it marked a shift in tone—from confrontation to guarded pragmatism.

Yet, these discussions underscored another unsettling reality: the marginalization of developing countries in major trade negotiations. African nations, in particular, remain on the sidelines, despite being disproportionately affected by the economic volatility such disputes generate. More troubling is Africa’s increasing absence from U.S. economic diplomacy under Trump’s renewed administration. While leaders from Europe, Asia, and the Americas feature prominently in high-level discussions, Africa’s representation remains minimal. This is especially alarming given that the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA)—a key pillar of U.S.–Africa trade—is set to expire in less than four months. If AGOA lapses without renewal or replacement, it would deal a severe blow to African exports, stripping them of preferential market access.

Against this backdrop, African countries and the broader Global South must reconsider the architecture of their trade relations. The answer is not disengagement from the U.S. or any one partner, but diversification—broadening trade relationships to enhance resilience and reduce vulnerability to external shocks. If the U.S. continues to turn inward, the Global South must increasingly turn to each other—and to global partners committed to multilateral cooperation.

The contrast with other regions is striking. Within the European Union, intra-regional trade accounts for more than 50% of total trade—and exceeds 75% in countries like Luxembourg and Czechia. ASEAN, though less integrated, maintains intra-regional trade at around 21.5%. In comparison, intra-African trade remains at a paltry 16%. This disparity reflects a fundamental structural weakness: Africa trades far more with external partners than within its own borders, making it particularly vulnerable to global crises, tariff shocks, and geopolitical tensions.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), launched in 2021, offers a critical path forward. If fully implemented, it could significantly increase intra-African trade, support industrialization, and create a single continental market for goods and services. However, this will require investment in infrastructure, harmonization of regulations, and political will to dismantle non-tariff barriers.

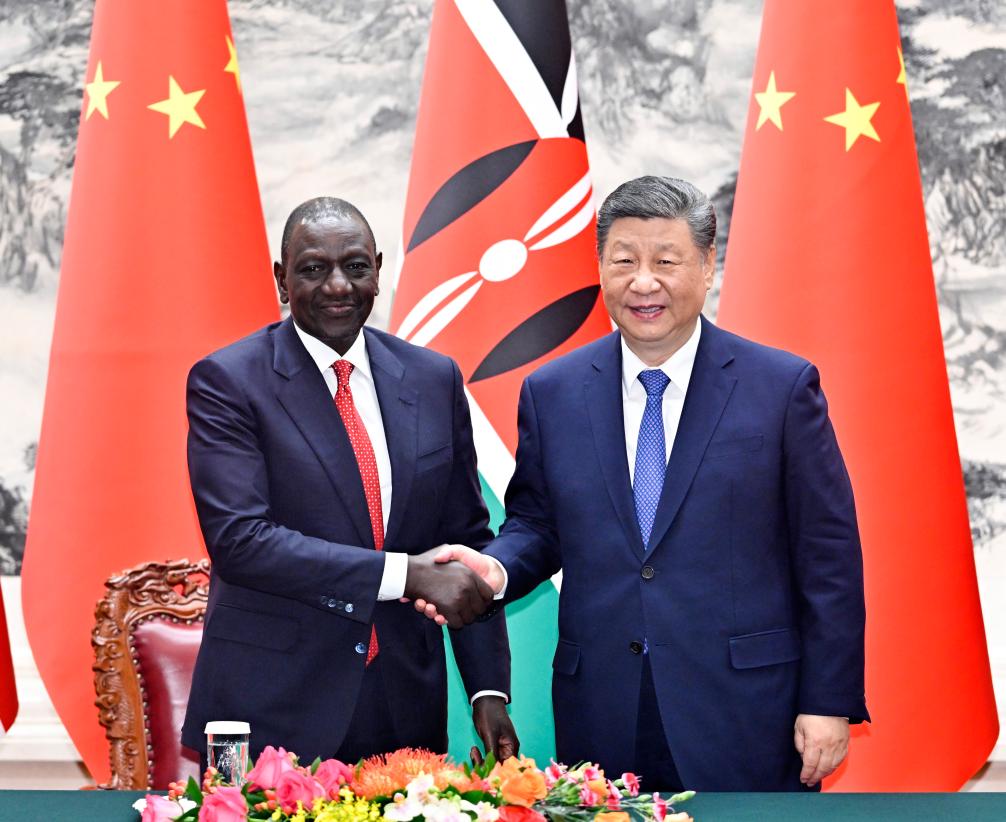

China has already stepped forward with initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), aiming to help close Africa’s $100 billion annual infrastructure gap. While these partnerships come with their own challenges, they reflect the kind of long-term, multilateral commitments that many African countries seek. Europe, too, is reassessing its alliances and expanding beyond traditional partners in response to U.S.–China tensions. The Geneva talks only reinforce the urgency for global actors to engage more meaningfully with the Global South—ideally through partnerships that prioritize sustainable development, not just geopolitical maneuvering.

Trump’s tariff-first strategy should serve as a wake-up call. Trade policy driven by nationalism and isolationism may appear attractive in the short term but often triggers global ripple effects, particularly in export-dependent regions like Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Africa. Tariffs may seem to bolster domestic industries, but they function as a tax on consumption—raising costs for businesses and consumers alike, and potentially fueling inflation.

Moreover, international trade is never a one-way street. Sweeping U.S. tariffs have already provoked retaliation. The EU, China, and other global powers have signaled or implemented countermeasures. These tit-for-tat spiral echoes the disastrous trade wars of the 1930s, which deepened the Great Depression and choked off global commerce. In today’s interconnected world, such a scenario would be even more destructive—especially for nations on the periphery of global trade.

In the end, Africa and other Global South nations must seize this moment to recalibrate. They must deepen regional integration, expand intra-regional trade, and seek out partners that prioritize cooperation over confrontation. The current crisis is both a warning and an opportunity: to build a more self-reliant, diversified, and resilient trade ecosystem capable of weathering the storms of great-power rivalry.

The future of global trade will not be determined solely in Washington or Beijing—but also in how decisively Africa and its Global South partners choose to shape their own economic destinies.

The writer is a Journalist and Communication consultant