NAIROBI, kenya, Dec 3 – When 61-year-old Kupata Kenga heard that the Community Health Promoter (CHP) had arrived for his monthly check-up, he hurried to his compound and settled under a tree outside his house—the familiar spot where their routine conversations about his blood pressure always begin.

Several months ago, he had no idea he was living with hypertension. Like many people with the condition, he felt strong and healthy. But during a community screening exercise in his village in Kilifi, health workers told him his blood pressure was dangerously high. “I was honestly very okay; I felt my body was doing great, but the health workers came and told me that there was something very wrong,” Kenga recalled.

Kenga is now among participants in the Improving Hypertension Control in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa (IHCOR) study, a research study in Kilifi that is evaluating how interventions involving community health promoters (CHPs) can improve early detection, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of hypertension—a disease often dubbed the ‘silent killer’.

Every month, CHP Cavalasco Charo rides nearly three kilometres to Kenga’s home in Matsangoni. Once Kenga settles down, Charo powers on his digital blood pressure device and prepares to take his readings. “Charo is a very good friend of mine; we talk a lot,” Kenga said.

Charo asks him to relax, places the cuff around his left arm, and waits for the five minutes required to get an accurate blood pressure reading. When the machine beeps, he reads the result: “124 over 70. His blood pressure is okay.” He then records the data, which feeds into the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust research project.

For Kenga, adjusting to life with hypertension has meant changing long-held habits. He admits his lifestyle contributed to the condition. “I used to wake up very early in the morning to drink until the evening. And I was also smoking a lot, like a pack of cigarettes every day,” he said. A father of six and once a renowned coconut harvester, he has shifted to lighter work, adjusted his diet, and is gradually reducing smoking and alcohol consumption.

According to the World Health Organization, an estimated 1.4 billion adults globally were living with hypertension in 2024. Many have no symptoms, making routine screening essential to detect the condition before it leads to complications such as heart attacks, kidney injury, or stroke.

The IHCOR study, launched in 2022, involves participants from Matsangoni and Chasimba in Kilifi, Kenya and comparable groups in Keneba, The Gambia. It is a collaboration between KEMRI-Wellcome Trust, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and the Medical Research Council Unit in The Gambia, targeting 1,250 participants across the two countries. Findings are expected in December 2025.

Unlike previous research studies, IHCOR relies heavily on CHPs drawn directly from the community. They were trained on consent, communication, and blood pressure measurement. CHPs then recruited participants from individuals randomly selected from the participating sites. After recruiting participants, those with high readings, were referred to the study clinic for confirmatory tests and assessment for organ damage.

Participants were categorised into three groups: those with normal readings receive lifestyle advice; those with elevated pressure but no organ damage get lifestyle advice and are reminded to regularly monitor their blood pressure; and those with confirmed hypertension and organ damage begin treatment immediately.

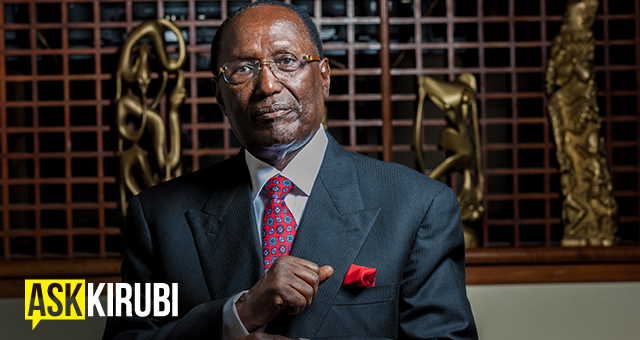

The study also evaluated whether using a single-pill therapy can improve adherence to treatment. The single-pill being tested was a combination of two hypertension drugs, amlodipine and perindopril. “The single pill is a convenient way to treat hypertension without having patients swallow many separate pills,” Dr. Ruth Lucinde, one of the study team members.

Dr. Lucinde hopes the study’s results will influence national guidelines and improve hypertension management in underserved areas. “Improving how individuals are identified, diagnosed, and treated may reduce complications from undiagnosed or poorly managed hypertension,” she said.

As Charo wraps up his visit, he commends Kenga for staying on track with his medication. Kenga, who admits he skipped a dose once, promises to remain consistent. “When I wake up every day, taking my medicines is always my priority,” he said. “Last week I forgot once because of a family function. I’ll make sure I carry them next time.”