By Aliénor Barrière

JAN 26 – At the end of 2025, Madagascar was the scene of a new political crisis. The removal of the president amid an electoral standoff, followed by demonstrations in Antananarivo and internet shutdowns in several tourist regions, plunged the sector into a sudden downturn. According to figures from the Ministry of Tourism, nearly 80 percent of bookings were cancelled between October and December, affecting hotels, tour operators, guides and restaurateurs. Madagascar, which had only just returned to its pre-Covid visitor levels, fell once again.

To counter this image of instability, the government rolled out an express communication campaign: television adverts, travel influencers and partnerships with artists. The aim was to tell the world that Madagascar is still there and ready to welcome visitors. But behind the smiling posters, the figures underline the violence of the shock: in 2024, a record 308, 275 international visitors set foot on Malagasy soil. This was already a victory after the Covid years, but 2025 weakened this momentum and operators are now banking on stagnation, or even a slight decline, in 2026. For good reason: tour operators do not take risks when the political situation is unclear.

Other obstacles add to this: violence remains widespread in Malagasy society and the junta strengthens its control of the country day by day. These factors do not encourage travel to the Big Island, especially as after more than 100 days in power, the military has still not resolved the recurring problem of power cuts. In this context, the tourism rebound remains a fragile dream, suspended between image and on-the-ground reality.

States investing heavily in nature-based tourism

A few thousand kilometres away, in Tanzania, the picture is very different. In 2024, the country surpassed the milestone of 5.3 million visitors, an all-time record, up 33 percent year-on-year. Parks, the beaches of Zanzibar, treks on Kilimanjaro… everything seems to attract visitors, as the figures confirm: 4 billion dollars in tourism revenues in 2024, the country’s leading source of foreign currency. Behind this success lies a methodically deployed strategy: promotional films, a strong social media presence, a simplified electronic visa. The Ministry of Tourism is targeting 8 million visitors by 2030, betting on diversification of the offer. Nevertheless, signs of fatigue are emerging. Infrastructure is struggling to keep up, roads to certain parks are impassable, and some sites are suffering from overcrowding. Another issue has been the violent electoral tensions in recent weeks, which have put the brakes on this upswing.

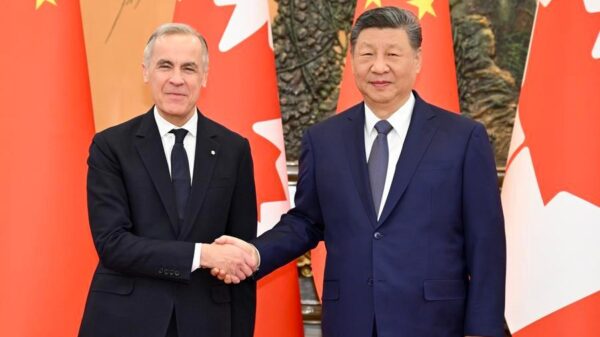

In Kigali, Rwanda is banking on rigour. There is no mass tourism here, but rather high-end stays with a permit costing 1,500 dollars to observe mountain gorillas. In 2024, 1.36 million visitors crossed the border. Fewer than in neighbouring countries, admittedly, but with solid revenues: 647 million dollars, one sixth of which came from conference and convention tourism (MICE). Designer hotels, immaculate roads, an airport under construction in Bugesera, the country is building itself an African showcase for premium tourism. Here, too, caution is required: the model is fragile, dependent on a handful of markets, and everything rests on the image of a safe country.

Nairobi, for its part, is playing the power card. With 2.39 million visitors in 2024, Kenya set a record: 3.1 billion dollars in revenues and more than 1.1 million direct jobs. A precious windfall for an economy under pressure. The government was aiming for 3 million tourists as early as 2025, relying on a diversified offer: safaris, coastline, business tourism, gastronomy. Wine tourism circuits are even beginning to appear near Mount Kenya. But the depreciation of the shilling is squeezing margins, and more remote regions remain neglected for lack of infrastructure. Here, again, the contrast between the showcase and the backyard raises questions.

That same year, around 870,000 tourists travelled to Mozambique, mainly from neighbouring countries. Revenues, meanwhile, stagnated at around 221 million dollars, far too little for a country with one of Africa’s richest coastlines. Despite a lack of connections and security in certain areas, the Bazaruto Islands and northern reserves attract visitors and the authorities believe in their potential: in 2025, they organised a tourism summit, introduced visa exemptions and promoted a tax to finance promotion. But the country is starting from a long way back.

With 1.37 million tourists and 1.28 billion dollars in revenues, 2024 marked a turning point for Uganda. It was the first time the country clearly exceeded one billion dollars in annual revenues. This performance was welcomed, even if visitor numbers remain below 2019 levels. The “Pearl of Africa” is banking on its gorillas, safaris that are cheaper than those in Rwanda, and a booming community-based tourism sector. Uganda has also modernised its offer with electronic visas, roads and marketing. Its government has made tourism a strategic development priority through to 2029.

A sector still bogged down by insecurity, political instability and inadequate infrastructure

Everywhere, the same words recur: fragility, dependence, a race for visibility. Indeed, while East Africa attracts visitors, it remains at the mercy of external—and internal—shocks. The Malagasy political crisis was a reminder: one overthrow, an internet shutdown, and everything collapses. Tourism is a hypersensitive sector.

At regional level, dependence on foreign flows remains massive. The African market is emerging slowly, but the United States, France, Germany and India still account for the bulk of solvent visitors. A global economic slowdown, a surge in airfares, or a poor rating in a UNWTO report can freeze months of promotional efforts. Some countries, such as Rwanda or Tanzania, are trying to diversify their client bases, Middle East, Asia, diaspora, but the equation is complex.

Infrastructure also represents a real weakness in these states: potholed roads, limited air access, outdated or undersized hotels. In Zanzibar as in Nosy Be, visitors complain about the same paradox: dream landscapes, but nightmare logistics. And major projects, airports, motorways, high-end hotels, suffer from a lack of coherent territorial strategy.

Added to this is a more muted challenge: that of distribution. Everywhere, governments boast of the billions generated by tourism; yet in rural areas, few see any of this windfall. Young people struggle to find stable employment in the sector. The risk of social backlash exists. By redistributing 10 percent of its park revenues to communities, Rwanda is trying to defuse this tension, but elsewhere, the sense of exclusion is growing.

Finally, climate change enters the equation. In Madagascar, cyclones are multiplying. In Tanzania, droughts are affecting ecosystems. In Zanzibar, erosion is eating away at beaches. The very model of tourism based on nature, wildlife, landscapes, coastline, is being severely tested. The need to shift towards sustainable tourism is no longer an option, but an urgency.

The tourism rebound is there, but fragile

East Africa captivates, fascinates and attracts. It ticks all the boxes of the traveller’s imagination, but it is walking a tightrope: between rapid growth and chronic vulnerability, between spectacular showcases and blind spots. Tourism could become a major lever for development in the region, or an unstable mirage. Everything will depend on the ability of states to guarantee stability, invest wisely and share the fruits of this industry with their populations. Failing that, the millions of visitors in 2024 may prove to be nothing more than a flash in the pan on the savannah.