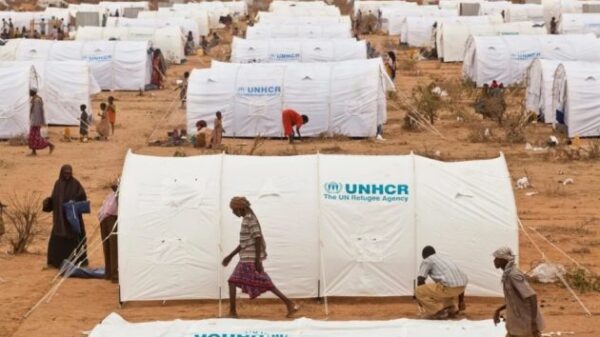

The entrepreneurs, who mainly use the online platform to conduct their business, admit that it is usually much easier to work with foreign investors/FILE

NAIROBI, Kenya, Mar 1 – You will probably read this story from the confines of your office, in-between university lectures, or as you take your mid morning tea after doing a heavy morning shift.

As you do so, Awil Osman, Esther Mwangi, Rodgers Muhadi and a dozen of other start-ups are at iHub, in Bishop Magua Centre figuring out how to make their start-ups into renowned companies.

As with most start-ups in Kenya and worldwide, the three youths have faced firsthand the challenge of acquiring funding to get their businesses off the ground.

Osman for instance, says that lack of an investor who will understand his situation has been tough.

“It’s not that there are no investors at all, there are. The terms they offer is however the problem,” says Osman, the Director of Sumuni Technologies.

A majority of local investors, as Osman says, are too impatient; “They want to put in little money into your business and call all the shots at the same time. A majority of them also want to get returns at the shortest time possible, probably in less than a year or slightly after a year which is almost impossible with any kind of a start-up.”

His sentiments are shared by Chris Orwa, a top researcher at iHub. He explains that a majority of local investors put in money into local start-ups with a ‘gambler’ mentality. “A majority put in money into these businesses the same way people put money into betting games where results are almost instantaneous.”

How about working with foreign investors?

The entrepreneurs, who mainly use the online platform to conduct their business, admit that it is usually much easier to work with foreign investors.

Rodgers Muhadi, CEO and co-founder of PayKind, has for instance seen the impact that foreign investors can have into your business. His business provides conditional remittance via e-vouchers that takes advantage of electronic money transfers.

“After less than four years of being in operations, my co-founder and I received funding from an American investor. This has given our company an opportunity to grow as we now have operations in the United States,” Muhadi says.

But how easy is it for these start-ups to get foreign investors and do they come that easy?

The answer is no.

Last week, Nisha Dutt, the CEO of Intellecap, which brought the just concluded Sankalp Entrepreneurship Summit to Nairobi said that one of the biggest challenges that start-ups in Kenya and across the continent face is that investors have a low appetite for risk. This means that they are not readily willing to put money into just about any project.

“Most of them also want to put a lot of money into a business, much more than you need at the moment when you are seeking the fund. A person could be saying they want to put in US$100,000 (Sh10mn) and in exchange, they will require a large stake at your company,” Orwa adds.

Osman on the other hand says that he would be more than happy to get that kind of funding, as long as the investor is patient enough. He explains that his business and those of a dozen others would flourish if they got willing investors who would give them enough time to grow the business and grow the returns.

Getting Investors

The government has been doing its part in promoting Kenya as an investment destination. As such, various business conferences such as the Global Entrepreneurship Summit and the Sankalp Entrepreneurship Summit have trickled into the country in search of the opportunities that the government has promised through outfits such as Brand Kenya and KenInvest. It has also organized local ones such as the Kisii Entrepreneurship Summit to reach entrepreneurs in counties.

Investors have in turn taken to those summits to find suitable projects to put their money into.

How, then, have these entrepreneurs taken advantage of these various pools of investors?

“I think that the initiative by the government to organize these entrepreneurship summits has been a great decision. I, for instance, have attended some and established meaningful contacts,” Osman says.

Esther Mwangi the Founder and CEO of Esvendo, which subsidizes cost of sanitary towels and baby diapers for people in urban settlements, agrees with Osman.

In her words, the summits have been important as they have first and foremost put Kenya’s investment arena on the map.

“Even if I have not gotten an opportunity to get an investor from those summits, I know others from iHub centre that have ended up with Silicon Valley investors.”

Others such as George Gathoni, who runs five businesses which include Build Brand and Nelson Kwaje who runs Web For All Limited, say that they use such summits to get into the minds of the investors. Gathoni says that he follows pitching sessions – entrepreneurs present their ideas to a panel of potential investors with the hope of getting funding – closely to learn what exactly investors are looking for.

Osman agrees with him. He says that he has in the past used another start-up’s pitching session to seal the loopholes in his own business plan. “Some of the questions that investors ask during those sessions can really outsmart you. Following them has therefore given me an idea into what could be asked by an investor and what they are looking for.”

The entrepreneurs hence urged the government to organize more summits and take them to other locations outside Nairobi, to cater to other start-ups across the country.

Does that mean that the summits have achieved their intended goals in their entirety?

“No, far from it,” Chris Orwa says adding; “In my opinion, the summits have barely scratched the ground. They have done well in marketing Kenya investment-wise, they have also secured investments for a number of start-ups, but they have hardly made the kind of impact that summits their magnitude are expected to make. For instance, attendance at these summits by local start-ups has been very low, so has their participation.”

He adds that several investors have come into the country with money in their pockets and gone back with it due to lack of ideas that interest them.

“A majority of our start-ups have great ideas but they have not mastered them well. Many of them end up blowing up their chances simply because they could not present their ideas in a manner that would make an investor interested enough.”

Orwa, who ran a start-up for a year before it collapsed owing to lack of sufficient funding, says that too many start-sups are at the same time afraid of opening up their businesses to investors. Like him, many are afraid that they will lose their power once investors come in.

“That was one of the fears I faced. I thought that by getting an investor, I would lose my voice over what and how I wanted things to be done in my business.”

He therefore urges start-ups to not fear letting investors put money into their businesses, asking them to conduct thorough research on their potential investors and draw up a guiding constitution that would rule the partnership.