BY MOHAMED WEHLIYE

The supplementary budget will cater for salary related expenditures amounting to Sh18billion, operations and maintenance of Sh8.2billion and Sh89.7billion for ongoing and new projects/FILE

Economic numbers can look scary and sound positively terminal when not probably understood. Trillion-shilling debt here. Hundred-billion shillings deficit there. Big, scary, numbers everywhere. They get even more scary when some respected economists dishonestly use them and put a spin to give the impression that the country is in a very precarious position and is perhaps on the verge of bankruptcy. It borders on intellectual dishonesty and is unfair to the public when for example people who should know better claim that Kenya rescheduled a $600m bank loan for another three months because it was ‘broke’.

This despite the fact the country has more than 10 times that amount in reserves that it could use to pay off that loan if it wanted to. Was some of the proceeds of the proposed Eurobond not supposed to retire these bank loans? So how does a timing issue and a simple debt management strategy make one conclude that the country is broke? There has been a lot of negative remarks on the state of our national debt. Is debt about to kill us as recent newspaper headlines and comments from some of our economists would want us to believe? What is our national debt situation like? Do the facts and figures support the views of those claiming we are choking with debt? Let us examine the same.

What is National Debt?

Whilst the issue of national debt is one of the most widely discussed, it is also often a misunderstood area. A lot of people are talking about the national debt, but few are explaining it. So what is it then? National debt is the money owed by a country to domestic and foreign lenders. It results from expenditures that exceed revenues. It is the running total of all deficits minus all surpluses, from Jomo to Uhuru Kenyatta. Contrary to what many people believe to be conventional wisdom, debt is actually a beneficial and recommended pursuit, if used correctly, since it enables a nation or an individual to equalize income and expenditures over time, and improve standards of living earlier than what would otherwise be attainable.

This is what individuals, corporations and countries do to improve their standard of living and shareholder’s net worth; by pulling their future incomes forward via borrowing. Show me a rich individual, corporation or a country and I will show you debt.

What is the acceptable level of National Debt?

Kenya’s national debt as at March 2014 was Shillings 2.172 trillion of which 1.231 trillion (56.6%) was domestic debt and Shillings 940 billion (43.4%), foreign. Our domestic debt is owed to commercial banks, pension funds, insurance firms, parastatals and other investors. The foreign debt is owed to foreign multilateral, bilateral, banks and other supplier credit sources.

So what does this 2.1 trillion number represent then? How big is it? Is it an inconceivable sum, far beyond anything that we could possibly handle? Two trillion shillings is definitely a lot of money but this headline number in itself isn’t important – until we place it in the proper context. Too big or too small in the context of national debt is relative. National debt must not only be benchmarked to the size of a nation’s economy or income but one would also need to look at a number of other factors such as its structure and cost of servicing in order to determine whether it has reached a ‘harmful’ level or not.

Kenya’s national debt as at March 2014 was Shillings 2.172 trillion of which 1.231 trillion (56.6%) was domestic debt and Shillings 940 billion (43.4%), foreign. Our domestic debt is owed to commercial banks, pension funds, insurance firms, parastatals and other investors.

First, national debt is usually looked at in terms of its percentage relative to the gross domestic product (GDP) of a country. There does not exist a threshold or a standard above which it will be considered too big but the conventional wisdom is that the higher the national debt relative to GDP the worse and vice versa. Some economist have gone a step ahead and through empirical studies, identified a “tipping point” for national debt – the point at which national debt levels begin to have an adverse effect on economic growth.

Based on an analysis of the debt of 100 countries over 30 years they found that once a country’s public debt exceeded 77 percent of its GDP, the amount of debt will have a linear relationship to declines in economic growth. In other words, the more debt you have above that point, the slower your GDP will grow. They found that if a country’s GDP is growing at a rate of 3 percent annually, and it increases its debt to GDP ratio from 80 percent to 90 percent, its economic growth will shrink the following year to 2.8 percent. That tipping point could be higher or lower for any specific nation, based on the nation’s wealth and countries with emerging economies and lower per-capita incomes were found to have a lower tipping point of around 64 percent.

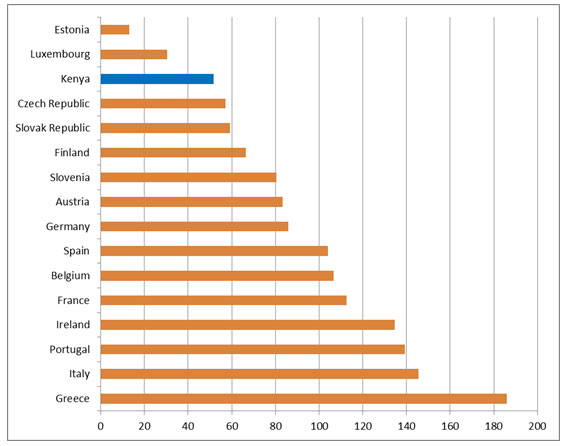

Kenya’s combined total debt was 52.2 per cent of GDP as at March 2014. It is worth bearing in mind, that other countries, although wealthier than us, have a much bigger ratio. To put things into perspective, Japan has a national debt of 227%, Brazil 57%, India 68%, UK 91% and Italy’s is over 140%. The US national debt is close to 101% of GDP. So in effect some of these countries owe more than what they make in a year but are not countries that you would consider ‘broke’ or about to go bust. The high levels of their debts relative to the size of their economies, does not mean their economies are on the road to ruin.

On the contrary, most investors in fact regard some of these countries, for example Brazil and India, as having robust economies with promising prospects for even more wealth creation.

The Eurozone was hit by a sovereign debt crisis in 2008. If Kenya was a member of the Euro-zone, only Estonia and Luxemburg would boast lower debt-to-GDP ratio. So we are not about to go the Greece way anytime soon.

Those saying we are almost broke today because of our debt levels must look at the history of our debt. If we are almost bust today, then we have almost always been bust. In Our debt relative to the size of the economy is not high by historical standards. In 2003 when the Kibaki administration came into office, the country’s debt stood at about 65% of GDP and was more than 300% of annual revenue. Today, Kenya’s total debt size is higher than it was a decade ago, but its debt ratio is much lower because total GDP is much larger.

According to the National Treasury’s own projections, Kenya’s Debt to GDP ratio is expected to decline in the medium term and be around 48% by the 2016/17 financial year. And this even before taking into account the rebasing of the country’s GDP to take into account the significance of new sectors of the economy.