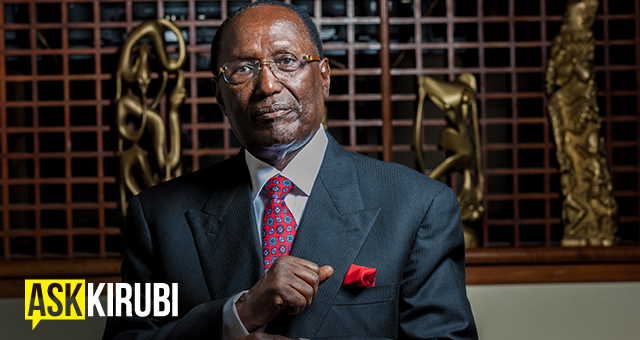

By Lydia Owuor

MAY 20 – Having worked in real estate law for fifteen years, when it comes to lease extensions, the most prudent approach is to apply for one at least five years before expiry. This rule of thumb exists for good reasons.

There is a crucial legal distinction between a lease extension and a lease renewal in Kenya. An extension, applied for before the lease expires, preserves the leaseholder’s legal interest and ensures continuity of title.

Renewal happens after expiry – by then, the land has escheated to the Government, the lessee’s rights have lapsed, and any new grant faces reallocation risks and new terms. Add delays at the land registry and issues like a co-tenant’s death triggering succession proceedings, and a routine process quickly becomes a legal minefield.

We won’t echo the flood of legal commentary on the Supreme Court’s 11 April 2025 decision in Harcharan Singh Sehmi & Another v Tarabana Company Limited and Others. Instead, we aim to clarify that the judgment reinforces what we’ve long advised as best practice – and to highlight its practical, commercial, and institutional lessons.

Briefly, three co-owners held leasehold property in Ngara, Nairobi, as tenants in common. The lease, granted in 1942, expired in October 2001. Though they claimed to apply for an extension in July 2001, they were evicted in 2014 by third parties with a new title. A lengthy legal dispute followed, complicated by the 2019 death of a co-tenant, whose case later abated.

The Supreme Court has now ruled, and from now on, any reference to the “appellants” means the two remaining co-tenants, the third having passed away.

To understand the legal and practical impact of the judgment, it’s essential to first look at the Supreme Court’s key findings. Once a lease expires without a formal extension, the land reverts to the Government. Filing an extension application before expiry—without completing the process—does not secure continued ownership. A title acquired through an irregular or illegal allocation cannot be legitimised, even by an innocent purchaser, and the doctrine of bona fide purchaser offers no protection where the root of title is flawed. Any legitimate expectation that a lease will be extended must be based on timely, documented, and properly supported administrative action.

The Supreme Court found that the appellants had a legitimate expectation their lease would be extended. Though the lease expired in 2001, they had engaged the Government and submitted the required application, which was acknowledged but never formally rejected.

The Court held that the appellants’ legitimate expectation could not be ignored without due process. It ruled that reallocating the property to third parties without resolving the appellants’ application was administratively unfair and a violation of that expectation.

The judgment notes that Harcharan Singh Sehmi’s appeal abated upon his death in 2019, and it appears that no substitution was made. Accordingly, only the two surviving appellants were granted relief in the judgment. This begs an important question: Can a deceased person’s estate benefit from a legitimate expectation that arose before their death, even where the underlying legal interest no longer exists?

By law, the property had to be returned to the Government when the lease expired in 2001. But there was no subsisting leasehold interest in 2019, and therefore, from a strict legal lens, the deceased’s estate could not claim a legal entitlement to reallocation. This is because legitimate expectation is not a legal interest or property right capable of transmission under succession law but rather a residual, procedural expectation that the Government might extend the lease.

But how do we balance citizen responsibility with institutional duty?

Regulation 3 of the Land (Extension and Renewal of Leases) Rules, 2017 requires the National Land Commission to notify landowners of imminent expiry of the lease tenure five years in advance – a measure designed to prevent the kind of uncertainty seen in this case. While the lease here expired in 2001, before the regulation existed, the rule signals a shift toward more proactive land governance.

This raises a key question: Should a landowner’s failure to renew their lease be judged in isolation, or alongside institutional inaction? It’s not about blame but rather about finding balance between citizen vigilance and consistent administrative practice – an issue future jurisprudence may need to confront.

Although the Supreme Court ultimately ruled in favour of the appellants, the lead-up to the dispute offers a sobering lesson. The lease was due to expire on 1 October 2001, yet the renewal application was only submitted on 13 July—less than three months before expiry. This delay left an unprotected window where the application remained unresolved, and no formal decision was issued.

As a result, the property reverted to the Government, which is standard with expired leases. During this procedural limbo, after the expiry but before renewal, the land was seemingly allocated to third parties, sparking a legal battle that lasted over a decade. This case underscores how timing, apathy, and administrative ambiguity can jeopardise even valid claims.

The writer is a partner in the Real Estate Law practice at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr (CDH) Kenya