NAIROBI, July 30 -Why does it take hours to travel from JKIA, Nairobi into the CBD? Why isn’t the Kenyan railway system efficient? Why is the Mombasa port congested? Why is doing business in Kenya so difficult?

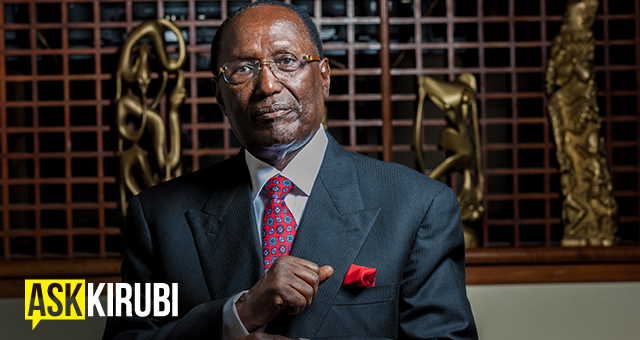

According to Harvard professor Michael Porter, who recently conducted an exclusive seminar for senior business leaders in Nairobi, dubbed “Microeconomics of Competitiveness”, Kenya’s economic problems are not so much a result of a lethargic government, but rather an attitude of “I must eat” possessed by many civil servants. While this is not new information to many Kenyans, it is interesting to note that a Harvard Professor, all the way from Boston, Massachusetts USA, is able to recognise these same issues that plague our country.

Porter suggests that for Kenya to be able to compete in today’s global economy, we must fix two things.

Firstly, our physical infrastructure including roads, railways, ports and telecommunications.

Secondly, we must enable and allow foreign direct investment into the country.

Kenyans have adopted the attitude that we should protect our local industries and are often suspicious of foreigners infiltrating the local economy. This has resulted in underperformance of local industries, because the environment has no real competition.

However, let’s take Telkom Kenya as a case in point. Formerly known as Kenya Posts and Telecommunications Corporation, it had enjoyed a monopoly for decades.

But then came Safaricom (partly owned by a foreign entity, Vodafone) and Celtel (owned by Zain, and formerly Kencel, owned by Vivendi Telecom). Their entries forced Telkom to wake up and perform!

What kind of foreign direct investment should Kenya embrace, I asked Dr. Porter?

In the past couple of years we have seen an increasing number of mergers, buy-outs and joint ventures between Kenyan and foreign companies, particularly with South African entities. Recent examples include CFC and Stanbic, Haco Industries and Tiger Brands, Swift Kenya and Altech Stream Holdings, Steadman and Synovate to name a few of the high-profile partnerships.

By partnering with these foreign companies, the Kenyan component benefits from technological and human resource expertise. In addition, not only does the Kenyan business benefit from capital injection, it is also able to tap into a wider distribution network for its goods and services, servicing a wider market. What this means for Kenyan enterprises is that their resource base is improved, creating a competitive environment for other players in the field to step up their game and meet these challenges. In the end, the consumer enjoys better prices, better quality of goods and services, and the government benefits from increased tax collection.

Porter stresses that welcoming foreign direct investment does not mean that foreign companies are given preferential trading grounds by the government; unfair competition never benefits the consumer or the government in the long run.

Porter preaches that governments should provide a level playing field for all players in the industry, and encourage foreigners to invest in Kenya. He gives the example of the United State of America, his home country, which has thrived on foreign direct investment that helped build it into one of the largest economies in the world.

Porter further points out that while Kenyan companies limit themselves to a population of 30 million Kenyans, multinationals operate on larger markets.

In conclusion, Kenyan businesses that are looking to compete globally should not shun partnerships, mergers or joint ventures with foreigners lest that be their downfall.