As a budding industry, film in Kenya stretches from small local productions to Hollywood blockbusters, but where does it stand now and where is it going in the future. By Caitlin Nordahl

Money, Money, Money

“Mberu Kimani [the chairman of 3rd Force, a major Riverwood production company] can do a film for you for $5,000,” Shamoon said, extremely matter-of-factly. And that’s the sort of budget that nets a profit in this region.

“The East Africa market is not big enough to pay for multi-million dollar films,” he explained, “We don’t have the audiences, we don’t have the distribution system.”

He thinks the money to support higher quality films, which might make it with an international audience, should come from the government. Mutie turns around and argues that “Quality is a factor of consumption,” meaning that as film quality gets better, people will expect better films and be willing to pay more for them.

Mutune, trying to push Leo from script to reality, took a different approach. Her first idea was to try and get the project produced by a Hollywood company, but while she received positive feedback, the answer was always no. Frustrated and Feeling she had done everything she could in the US, she decided to take the project back to Kenya and look for investors here.

While it may seem like a sound idea to look for Kenyan investors for a film so clearly rich in Kenyan culture, whose director had an eye on foreign distribution, it’s simply not a done thing here. Yet.

“We haven’t embraced film as an investment area in this country,” Mutie said,

“I haven’t heard of any feature production that has been supported that way.”

But after two years of searching, Mutune did manage to find enough to cover her budget of around US $200,000.

“It comes actually from local Kenyan investors – surprise, surprise – yes, they have money for movies,” she laughed. “The movie industry is something new to them, it’s not perceived as a money making engine, and so I had to pitch that side of it. But really most of them were sold on it because they felt that it was time for us to begin telling our stories from our perspective.”

Making a Movie

A turning point in the planning of Leo was when Mutune found her director of photography, Abe Martinez. A Hollywood trained American, Martinez is one of very few non-Kenyans involved in the project, although between frequent visits over the years and plans to move his family to Nairobi, he may qualify for unofficial status.

“We haven’t embraced film as an investment area in this country.”

Martinez had worked behind the camera, although not as the director of photography, for years in Hollywood on films like Ali and Spiderman III, so his signing on was certainly a huge boost to the production.

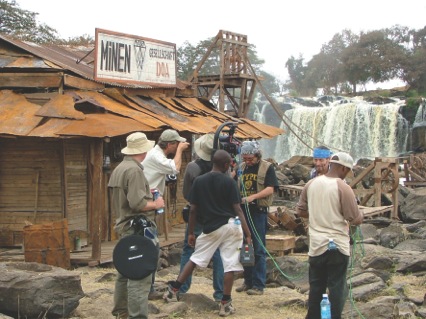

Conversely though, foreign productions are more and more often relying on local crew members and actors. Shamoon, whose company’s first feature film was Lara Croft Tomb Raider: The Cradle of Life, said that production brought in 200 people on a jumbo Jet with eighteen trucks worth of equipment. A few years later when they were hired for The Constant Gardner, the entire incoming crew consisted of 32 people, and six of them were actors.

Fernando Meirelles, the director of The Constant Gardner, used the local crew as a strategy to tell a more authentic story.

“In Kenya, the faces of the people, the colors, I wanted to bring as much of the landscape to the screen as I could,” he said. “That’s why I thought we should shoot in Kenya with a small crew – you just turn the camera around, and the real thing is happening here. If you do it big – lights, crew – you turn around and there’s only crew, and it affects everything all around.”

Kenya is reaching the point where there are enough professional crew members to support multiple productions. While sometimes the group of established crew members who have made their careers in the film industry gets stretched thin, there are many more than there used to be. Also, the more productions coming in, the more people get trained, the larger that professional group becomes.

And there is a strong appeal for using local crews: they’re much cheaper. As long as foreign productions can be guaranteed the same level of skill, they will continue to employ Kenyans.

Mutune’s US $200,000 budget, which she had to scrape together, is a fraction of what some Hollywood productions use (compare it to The Constant Gardner’s US $25 million or Tomb Raider’s US $90 million, according to estimates).

Yet she said, “In Africa, I found you could actually take that budget and make it work.” Undoubtedly this has to do with the skill and dedication of the crew available here.

Martinez, with his Hollywood background, is able to compare the different crews he’s worked with.

“In Nairobi, shooting there, I love it because my guys have ingenuity,” he said with pride, “Your limitation is sometimes your greatest strength, because it’s building you to be a better storyteller.”

Another point he was eager to make was that there was a definite dedication and thirst for knowledge on the sets of Leo. Mutune echoed the sentiment, saying, “I liked the mixture I had – I had very experienced and not so experienced, so the experienced taught the non-experienced the skill. And they were committed. My crew was committed, they believed in me all the way.”

Getting it all Out There

It takes a lot to get a Kenyan film released in cinemas, and they usually don’t do so well. In fact, Kenyan films that are screened in the country are often shown by cultural associations started by foreign countries, like the Alliance Française. For the most part, Kenyan productions follow the Riverwood system of distribution – straight to DVD and out to small stores, and sometimes the streets.

As Martinez put it, “The old ways of distribution, the Hollywood way – you see where that path is in Africa and it’s piracy.” And he’s got a point. Hollywood films are shown in cinemas but their main form of distribution here is in pirated copies, which brings up some unique problems for local films. Mutie even considers it to be the industry’s biggest robber of resources.

Because of the bootlegging, Mutune isn’t even launching her movie in Kenya, despite the effort she went through to painstakingly inject it with as much Kenyan influence as possible. Instead, she is looking to release in a select few foreign cinemas and hope that it gets picked up there, as well as entering key film festivals to garner attention. If it does well, she hopes to bring it back home.

It’s not all doom and gloom in Kenya though. With the advent of digital cable and the new content law saying that free to air channels must have 40% local content, television is opening up a huge market.

This is part of the reason Shamoon is so confident in Riverwood productions. “Everyone with a channel is going to need content,” he explained.

Another benefit: with local producers getting paid directly by stations instead of counting on DVD sales, budgets and the demand for quality could soon be on the rise.

Where Do We Stand?

While this is an exciting time for film in Kenya, there are some potential potholes along the road.

The new National Film Policy that Mutie is touting? Yes, an original draft has been made, but there still needs to be a meeting with industry stakeholders to approve and sign off on it (which has been postponed) and that’s not even close to the last step.

Meanwhile, with the new Constitution adopting the counties system, the policy will likely have to be changed to accommodate that. All in all, Shamoon doesn’t see it getting passed any time soon.

In addition, there is still more that government policies could do to support the industry. There are other countries in Africa that offer better tax breaks to foreign production companies coming in, and some of the incentives Kenya does offer are flawed. For instance, in 2009, a policy was introduced that removed the V.A.T. tax from cameras brought into the country. The lenses, however, were not included, and they can often cost more than the camera body.

“The East Africa market is not big enough to pay for multi-million dollar films,”

But through all of this there are still people fighting to build up the film industry because of the role it could have in Kenya. Mutune, enthusiasm and passion nearly bubbling over, said it best:

“That’s what I want to do for Kenya, and in large for Africa – I want to sell it as that ideal world. So that people will see it and say, ‘Wow, I want to try that food, I think I want to try that dress, I want to try their music, did you see it in the movie?”

First published in the February 2012 issue of Destination Magazine

For more articles like this one, check out Destination Magazine and on Facebook – Celebrating our unique culture and fascinating history while investigating issues pertinent to East Africa.