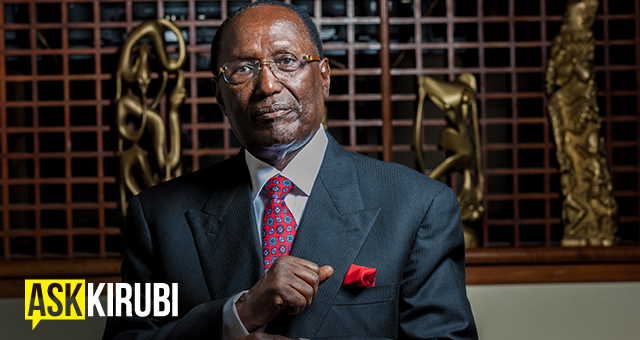

NAIROBI, November 20 – Few Kenyans know much about Wajir, aside from its location in a hot, dry region in the North of the country.

Yet it is here in a sandy-floored school lacking proper walls or windows that a young Abdisalan Noor first learnt about science.

Today, Dr Abdisalan Noor sits in his laboratory at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), surrounded by computers and other high-tech equipment he uses in his work as a research scientist, finding new ways to more effectively fight the burden of malaria in Africa.

His is a story of beating the odds, and succeeding in an arena where few Kenyans have made their mark at the global level.

Dr Noor grew up the ninth in a family of 27 children, spending time with his brothers looking after his father’s camels and cattle or minding the small shop in the village. Yet he distinguished himself by becoming the second person from his village, and one of the few from Wajir district, to attend a national secondary school.

It was at Mangu High School where a young Noor developed interest in sciences leading him to study for an engineering degree at the University of Nairobi. He majored in geospatial modeling, a new discipline at the time.

Dr Noor followed this with an unpaid internship at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) in Nairobi, where he gained practical experience in using computer software to solve real-life problems.

“ILRI offered me the chance to get practical experience using powerful computers and advanced software,” he candidly remembers.

“At the time, it was the only place to do geospatial modeling in Kenya. Having no salary was no reason not to do it,” he says.

Geospatial modeling mixes maps with other information to create visual representations of different things. Using additional data scientists can, for example, show on a map how long it takes for a person in a particular area to reach a hospital or how many malaria patients there are in a certain place, all in relation to roads and the location of major towns, hills or valleys.

This helps to clearly show where healthcare resources are concentrated and where gaps exist.

Dr Noor’s determination to learn these complex techniques, as well as his keen eye for detail, hard work and passion for the subject, landed him a post as a research assistant at KEMRI. His first project was to develop a national map of public and private health services, which had not been updated since 1959.

The success of the project gave him confidence in defining and addressing health-related issues.

He embarked on a PhD at the UK-based Open University which provided him with the chance to work with scientists at the University of Oxford to develop models of how far Kenyans travel to seek medical assistance.

After completing his PhD in 2007, Dr Noor won a prestigious international research fellowship from UK medical charity, The Wellcome Trust.

The award gave him the opportunity to further develop his research, investigating areas that interest him.

“The fact that I can do this from Kenya and not from abroad has been especially important for me; Kenya is my home and I have been able to pursue my dreams to become a research scientist in the country I want to make a difference in,” he proudly states.

The schoolboy who once walked to school barefoot along dusty roads is now part of an international research team, traveling to many countries in Europe, Africa and Asia. He provides advice on malaria mapping to define control strategies to Governments and aid agencies in Djibouti and Somalia.

“I have traveled to places I would never have visited, met some great people and earn a reasonable living. I enjoy my job and this is something I guess few people can claim,” he concludes.