NAIROBI, October 27 – How will sub-Saharan Africa be affected by the current global turmoil? There are two main transmission mechanisms: the financial market effect and the real economy effect.

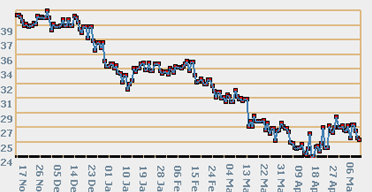

Although many African currency markets have sold off in recent days, reflecting the increasing importance of foreign portfolio investors during the boom years, sub-Saharan markets ex-South Africa – the so-called ‘frontier markets’ – remain amongst the most illiquid of emerging or pre-emerging countries, granting them a certain degree of resilience to the global crisis.

It is unlikely that the outflow of portfolio funds will have much economic impact beyond the near term. The region’s lack of deep financial linkages with the rest of the world has meant that the financial-market effect of the crisis has been fairly limited. It is the real economy impact that is of greater concern.

Traditional analyses of African economies have made much of Africa’s role as a commodity producer, and its dependence on commodity prices. The past performance of African economies certainly suggests that there may have been something to this linkage. For much of the last 30 years at least, each time the global economy experienced a slowdown, Africa appears to have experienced a more pronounced decline. But this time, things are expected to be different. The IMF recently cut its global growth forecast to three percent for 2009.

Growth in sub-Saharan Africa, with many countries starting off a much lower base, is expected to hold up at twice this level, at least at six percent. If commodity prices, susceptible as they are to the global slowdown, were the main driver of African growth, this would be curious.

In truth, the drivers of Africa’s growth appear to have changed. Africa’s recent history of domestic economic reform and macroeconomic stabilisation has seen a take-off in levels of private consumption. A brief examination of Africa’s recent growth record demonstrates how difficult it is to identify commodity prices as the key determinant of African growth.

Growth has picked up in both resource-rich and non-resource-rich economies. Many of the region’s oil importers have experienced significant terms-of-trade declines, for example, but have still managed to grow at faster rates. In these instances, net exports have often made a negative contribution to growth.

A study done by Standard Chartered Bank plotted recent growth against terms-of-trade developments for all the African economies for which good data is available. The findings were startling: there was no apparent relationship, positive or negative. The breakdown of GDP suggested that, while increasing levels of investment and government spending (not entirely unrelated to the commodity boom) had made a positive contribution to growth, the most significant factor tended to be the rise in private consumption.

It is in the context of the importance of consumption that the recent rise of inflation in the region is a big concern.

The headline-grabbing aspect of Africa’s reform programme and the macroeconomic stability that gave rise to faster growth was, of course, lower inflation. This provided a boost to disposable incomes, with private consumption levels posting real gains as a consequence. But Africa’s recent food- and fuel-related inflation shock is worrying. Although there is some evidence of a decreasing energy intensity to African growth, demand for food proved to be far more inelastic with respect to price.

Food dominates African consumption baskets, and CPI inflation has spiked. Despite the expected decline in commodity prices, we think it is unlikely that sub-Saharan Africa will see average inflation in the single digits either this year or next. Even the achievement of single-digit inflation in 2010 is looking somewhat doubtful.

The problem? Not only the recency of Africa’s macroeconomic stabilisation (suggesting that low, single-digit inflation may not be embedded in expectations), but in many instances, the fiscal deterioration that has accompanied food price strength.

Rising import prices are hitting the more politically mobilised, urbanised African population the hardest. Many countries have seen food-related riots.

It is no surprise that governments have reacted, sometimes waiving import tariffs on food items, sometimes taking the more economically damaging step of subsidising food (helping to kill off any potentially favourable supply response to higher food prices). The problem, in the context of African economies, is the generally weak tax base.

Once import tariffs are waived, there is generally no revenue to replace it with very readily. Some degree of fiscal deterioration ensues. If fiscal consolidation helped to bring about single-digit inflation in Africa, the opposite trend poses a key threat to inflation, disposable incomes, real consumption, and ultimately growth, at a time when African economies are at their most vulnerable.

It is of course difficult to generalise across all of Africa, and the 48 different economies that make up sub-Saharan Africa. But a brief overview of some of key African markets that have enjoyed a significant share of investor focus demonstrates that, even in these economies, fiscal policy might be increasingly problematic in the years ahead.

In the future, external influences will be more difficult. Policy will be tested in ways that were largely absent during the benign years of easy liquidity and record net capital inflows into many of these markets. Donor financing may traditionally have helped to fill a gap, but official development assistance (ODA) may be the first casualty of the deterioration in public savings that we now see in many of the major economies.

Against this backdrop, it is crucial to assess the extent to which fiscal prudence has taken hold in key sub-Saharan economies. The results are varied, as we show below.

Country Score Comment

Botswana A

In Africa, Botswana’s record on fiscal saving is difficult to beat, with budget deficits the rare exception rather than the norm. Even so, economic growth is dependent on government spending. Passage of the Fiscal Rule a few years ago limited government spending in any one year to 40% of GDP.

However, fiscal revenue in diamond-dependent Botswana is more vulnerable than most to a US economic slowdown. US demand is thought to account for at least 50% of the gem diamond market.

Nonetheless, with the ZAR – the main component of the BWP basket – expected to weaken against the USD, the BWP value of USD-denominated fiscal receipts may still see a boost, helping to sustain local-currency spending levels.

Ghana C

Following the 2001 elections, Ghana distinguished itself with the speed of its fiscal reform, qualifying for debt relief and helping to bring inflation down from over 40% to the low double digits. The 2004 elections were notable for the absence of any fiscal deterioration. But the increase in the public sector wage bill in 2006, spending in response to drought and energy crises in 2007, and fiscal measures triggered by high food and fuel prices in 2008 have all seen a widening of the fiscal deficit.

Rising inflation, currency volatility, and the withdrawal of foreign bond investors from the Ghanaian market have seen short-term rates surge to over 24 percent and sources of longer-term financing dry up, adding further pressure to the fiscal balance.

Even with a landmark privatisation, the deficit this fiscal year is likely to exceed 9 percent of GDP. While significant oil production is expected to commence in the medium term, the credit crunch and restrictions on Ghana’s ability to borrow against future oil earnings will constrain any meaningful improvements in its fiscal balance.

Kenya C+

Kenya has seen reform of sorts in recent years. With a well-established private sector and revenue-to-GDP ratios that compare favourably with the region, it has been more resilient than most.

Efficiency improvements at the Kenya Revenue Authority have resulted in significant gains, which, combined with a rebalancing of expenditure in favour of greater development spending, have helped boost Kenyan growth even in the absence of donors. This fiscal year, Kenya has set out an ambitious budget involving infrastructure spending, likely to deliver a deficit of 5.3 percent of GDP.

Plans for Eurobond issuance to finance the deficit may now depend on market conditions, with the global financial crisis and the widening of sovereign spreads on African EMs a negative factor. With a more developed domestic institutional investor base than most sub-Saharan markets, Kenya at least has other options. Even so, higher domestic debt financing costs should the planned Eurobond fall though would likely exert further pressure on the fiscal deficit, limiting room for future spending increases.

Nigeria C

Only a few years ago, Nigeria, reaping a heady hydrocarbons-fuelled windfall, and significantly saving the oil windfall for the first time in its post-independence history, was something of a poster child for sub-Saharan fiscal reform. Attempts to increase transparency in oil revenue also helped the fiscal effort.

However, much has changed in recent months, with Nigeria’s political class increasingly focused on the country’s gaping infrastructure deficit.

Earlier this year, Nigeria’s National Assembly voted to limit the extent of windfall savings to only 20 percent of previous levels, with 80 percent to be shared amongst the three tiers of government (federal, local, and state), resulting in disbursements from the Excess Crude Account. With subsequent moves to increase the budget reference price of oil (it has been set at $56 for the 2009 budget, down from $59 the previous fiscal year), the rate of oil windfall accumulation has also declined.

Although there have been some successes under the Yar’Adua regime, notably the repayment by ministries of unspent funds, Nigeria must now deal with the possibility of further declines in the price of oil. Having already cut its rate of fiscal saving, and with the risk of continued output shortfalls making it more dependent on offshore fields that yield less government revenue, Nigeria is now more vulnerable to a downward correction in the price of oil.

South Africa A

Post-apartheid South Africa’s reputation for fiscal conservatism is now well-established, and the reappointment of Trevor Manuel as Finance Minister – a conscious policy decision by the new ANC leadership – has helped calm market fears of a potential change in policy.

Nonetheless, South Africa is likely to see its announced budget surplus for FY 09/10 entirely eroded when the Medium Term Budget Policy Statement is delivered at the end of October. Not only is sluggish growth likely to weigh on fiscal revenue, but planned expenditure on state utility company Eskom is likely to exceed the contingency reserve set aside for electricity spending, the previously planned surplus, and at least another R10 billion.

Compounding matters, Eskom’s planned international bond issuance programme, necessary for its recapitalisation, has been delayed due to adverse market conditions.

There is now a higher risk of reliance on state guarantees, a quasi-fiscal measure that would constrain the financing available for other infrastructure projects. Despite the best intentions, South Africa’s small fiscal surplus is likely to fall victim to the global economic crisis. Relative to its peer group, however, the country at least has no costly banking system bailout to contend with.

Tanzania B

Traditionally reliant on donor financing following its emergence from socialism, Tanzania has in recent years made rapid progress in increasing domestic revenue collection. Robust growth, increasing diversification of its economy, and a more ‘identifiable’ private sector following initial difficulties in its economic transition have seen a steady increase in Tanzania’s revenue-to-GDP ratio.

Despite this, donors still account for a large proportion of budget financing, and the country’s prospects would be visibly affected by any pullback in Official Development Assistance. Tanzania’s resistance to liberalisation, in particular opening up to foreign portfolio investment, increases its vulnerability. Liberalisation would open up other sources of funding even in a more difficult external environment.

Uganda B

Compared with Tanzania, Uganda has not made much progress in increasing domestic revenue collection, with ratios still around 13 percent of GDP. This represents a key vulnerability in Uganda’s fiscal

outlook.

Although donor assistance has been forthcoming, with Uganda seen as an African success story that donors have been keen to support, development financing is likely to be one of the key casualties of the global economic slowdown. Already highly liberalised, Uganda has done well to attract increasing yield-seeking portfolio flows in recent years. But the onset of the global financial crisis has seen a pullback by investors even from traditionally favoured African markets. Longer-term, there are few alternatives to boosting domestic revenue collection.

Zambia B+

Considered a relatively late reformer, with the size of its public-sector wage bill threatening IMF support in 2003, Zambia has made great progress recently. Fiscal reform allowed it to qualify for sweeping external debt relief in 2005. In 2008, Zambia imposed a windfall tax on copper mining companies, but did not include revenue from the tax in its budget plans.

The intention was to save the proceeds. More recently, the country has made concessions to the mining sector, taking production costs into account in the calculation of the windfall tax, helping to ensure the long-term viability of the sector.

When windfall revenue is included, Zambia’s budget may be in surplus.

Although a decline in copper prices is anticipated as a result of the global slowdown, reducing the overall size of the windfall, Zambia has at least created an important source of longer-term savings for itself. The planned doubling of copper output in the medium term, and a healthy rate of revenue collection from the non-mining sector, leave Zambia relatively well-placed, although still vulnerable to a decline in ODA.

The examples above show the difficulty of generalising about Africa, but also highlight some of the common threats that many of Africa’s economies will face: weaker commodity receipts in resource-rich countries, potentially lower levels of ODA in donor-dependent countries, and less easy financing from global investors.

Against these constraints, African economies must still attempt to stay on the path of fiscal conservatism, keeping inflation under control whilst maintaining all-important infrastructure spending. Something will have to give, and despite overall optimism that African growth is unlikely to collapse, the years ahead will be more difficult. While more resilient to the global slowdown than other developing regions, Africa will still face its share of hurdles, with the more difficult external environment only highlighting homegrown vulnerabilities.

This report was prepared by Razia Khan, Regional Head of Research for Africa at Standard Chartered Bank