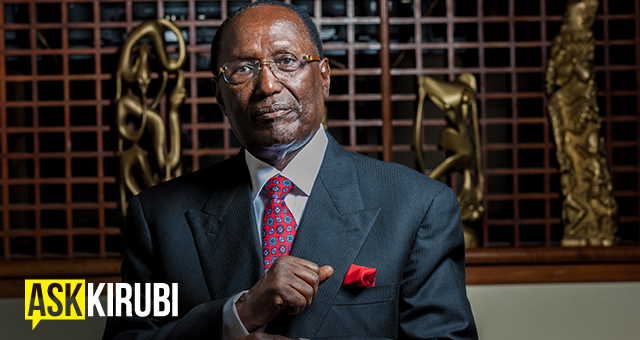

It is sad to note that some economists still use the argument that Kenya’s Debt to GDP ratio is well above that of Sub Sahara Africa (around 35%) when discussing Kenya’s national debt. This is despite them knowing very well that many of the SSA countries benefited from debt relief in the last decade under the framework of the Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative . Kenya did not benefit from debt relief partly because its debts have been manageable and the country has long been considered better off than many of its neighbours and not in need of such assistance. Kenya’s higher than average ratio is therefore very much a victim of its good management of debt. Others including our neighbours Tanzania and Uganda were rewarded simply because they didn’t manage theirs well.

Debt structure matters.

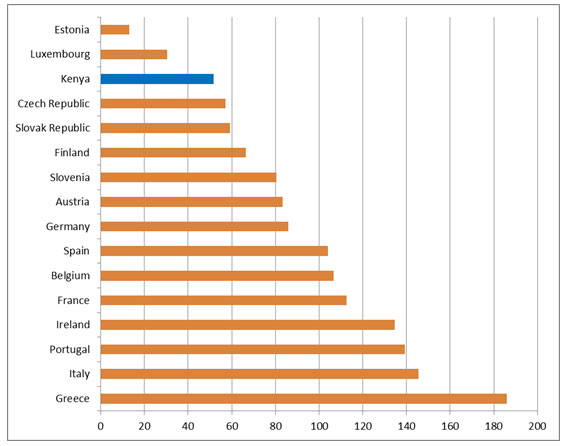

Countries usually aim to have a higher percentage of their national debt as domestic debt. As at March 2014, almost 57% of the national debt was held by local commercial banks, insurance companies, parastatals building societies and other domestic investors. The remaining 43% was foreign debt. The lower the external debt compared to the internal debt the better. Partly this is because when the debt and its interest are repaid to domestic creditors, part or all of it stands a bigger chance to be invested domestically and generate economic activities. Servicing the debt (paying interest, issuing bonds) therefore just redistributes income from Kenyan taxpayers to mostly Kenyan bondholders. It is not necessarily money leaving the country.

The domestic debt is also no longer dominated by short term and excessive inflationary biased method of deficit financing as it was during the Moi era. It has now more long term debt component than it used to do. Treasury has in the last decade sought ways to lengthen the average maturity of its domestic debt from 12 months to almost 5 years. By going long-term, the government has lowered the refinancing risk meaning there is less pressure to refinance the debt at any one time.

Kenya’s foreign debt (before the recent Chinese deals) on the other hand is mainly concessional and long-term, with an average maturity of 32.6 years and an average interest and grace period of 1.1 percent and 7.5 years respectively at the end of March 2014.

Countries usually aim to have a higher percentage of their national debt as domestic debt. As at March 2014, almost 57% of the national debt was held by local commercial banks, insurance companies, parastatals building societies and other domestic investors. The remaining 43% was foreign debt.

Kenya’s external financing sources is also well diversified and the country does not have big exposures to any individual creditor country. The World Bank and the African Development Fund are the two biggest creditors with the rest of the foreign debt almost equally distributed across geographically diverse economies.

Debt Sustainability is the single most important factor

Whereas the raw amount of debt accumulated is what captures the headlines, the real risk from government debt is the burden of interest payments. We can remain perpetually indebted so long as the interest payments we make don’t go out of control. Whereas we have loaded big sums of debt in the last few years, interest rates during this period have been about as low as they have ever been. We borrowed many times what we used to borrow a decade ago at a fraction of the cost we used to borrow at and the weighted average interest rate on Kenya’s national debt as at March stood at 4.7%. The debt’s current cost to taxpayers is therefore about as low as it has been in decades.

The yearly interest expense on our national debt relative to GDP is a key indicator of debt sustainability. The National Treasury is expected to spend about 154 billion shillings at the end of this financial year to service the national debt. That equates to a debt servicing as percentage of GDP ratio of around 3.7%. Not a high ratio by any standards. Experts believe that when interest payments reach about 12% of GDP then a government will likely default on its debt.

Another way to look at sustainability of debt is to compare annual servicing cost to development expenditure. The amount we will use to service the debt in this financial year (Sh 154b) is far lower than the amount the country has earmarked as development expenditure (Sh 448b) during the same period. This means debt servicing has not yet reached a point where it has limited the country’s capacity to fund its development and other emerging priorities or required us to seek heavy donor involvement.

The Joint World Bank-IMF Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA) for 2013 has also given Kenya’s public debt thumbs up. DSA assesses how a country’s current level of debt and prospective new borrowing affects its ability to service its debt in the future. According to these two institutions, debt sustainability can be obtained by a country “by bringing the net present value (NPV) of its public debt down to within a certain threshold of its GDP and revenues”.

Kenya’s NPV of Dept as a percentage of GDP in 2014 was assessed to be at 39% against WB/IMF thresholds of 74%. Against revenues, the ratio was at 151% against a 300% threshold. Further stress testing indicates that Kenya’s NPV of debt/GDP ratio would still be within WB/IMF debt sustainability thresholds in the medium term even if it increased its borrowings now by another 10% of its GDP. This means that the planned Eurobond issuance and the uptake of the recently contracted Standard Gauge Railway loan will not breach Kenya’s debt sustainability thresholds or modify the favourable conclusions of the last WB/IMF Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA) on Kenya’s external and public debt position in the medium term.

Kenya’s debt has thus far been well managed and the country has in the last decade implemented wise fiscal policies and sound budget management. But managing the debt will now become tougher than before.

The government will need to maintain fiscal prudence while continuing to invest in infrastructure and fund devolution. It will also has to ensure that foreign exchange risk is well managed given that it will now have a foreign currency denominated bond (Eurobond) in its books.

This perhaps poses the greatest risk to debt sustainability in the foreseeable future. But a sustained focus on making the cake bigger through economic growth is what will guarantee that Kenya’s debt levels continue to remain sustainable. As it stands now though, all the relevant indicators and other parameters of our national debt show that we are nowhere near being broke. People who are saying the country is broke should be very careful. We should not over politicise the economy. The economy is a very precious thing to any country. The fact that we still hold a good credit rating and lenders continue to lend money to us is an indication that lenders not only don’t believe the government is broke right now, but also don’t see bankruptcy anywhere on the horizon.